In April I wrote here on the draft science assessment guidance from the TAPS group. The final version is now out in the public domain (pdf), described thus:

“The Teacher Assessment in Primary Science (TAPS) project is a 3 year project based at Bath Spa University and funded by the Primary Science Teaching Trust (PSTT), which aims to develop support for a valid, reliable and manageable system of science assessment which will have a positive impact on children’s learning.”

I was vainly hoping for a miracle: valid, reliable AND manageable! Could they pull off the impossible? Well if you read my original post, you’d know that I had already abandoned that fantasy. I’m sorry to be so disappointed – I had wished to be supportive, knowing the time, effort (money!) and best of intentions put into the project. Others may feel free to pull out the positive aspects but here I am only going to point out some of the reasons why I feel so let down.

Manageable?

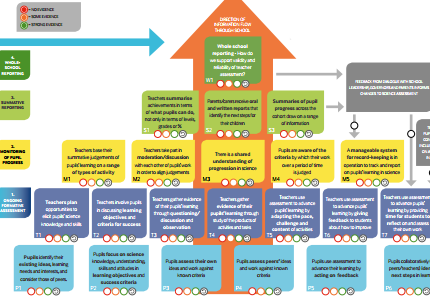

At first glance we could could probably dismiss the guidance on the last of the three criteria straight away. 5 layers and 22 steps would simply not look manageable to most primary school teachers. As subject leader, I’m particularly focussed on teaching science and yet I would take one look at that pyramid and put it away for another day. Science has such low priority, regardless of the best efforts of primary science enthusiasts like myself, that any system which takes more time and effort than that given to the megaliths of English and Maths, is highly unlikely to be embraced by class teachers. If we make assessment more complicated, why should we expect anything else? Did the team actually consider the time it would take to carry out all of the assessment steps for every science objective in the New Curriculum? We do need to teach the subject, after all, even if we pretend that we can assess at every juncture.

Reliable?

In my previous post on this subject, I did include a question about the particular assessment philosophy of making formative assessment serve summative aims. I question it because I assert that it can not. It is strongly contested in the research literature and counter-indicated in my own experience. More importantly, if we do use AfL (assessment for learning/formative assessment) practices for summative data then in no way can we expect it to be reliable! Even the pupils recognise that it is unfair to make judgements about their science based on their ongoing work. Furthermore, if it is teacher assessment for high stakes or data driven purposes then it can not be considered reliable, even if the original purpose is summative. At the very least, the authors of this model should not be ignoring the research.

Valid?

Simply put, this means ‘does what it says on the tin’ – hence the impossibility of assessing science adequately. I’m frequently irritated by the suggestion that we can ‘just do this’ in science. Even at primary school (or perhaps more so) it’s a massive and complex domain. We purport to ‘assess pupils’ knowledge, skills and understanding’ but these are not simply achieved. At best we can touch on knowledge, where at least we can apply a common yardstick through testing. Skills may be observed, but there are so many variables in performance assessment that we immediately lose a good deal of reliability. Understanding can only be inferred through a combination of lengthy procedures. Technology would be able to address many of the problems of assessing science, but as I’ve complained before, England seems singularly disinterested in moving forward with this.

Still, you’d expect examples to at least demonstrate what they mean teachers to understand by the term ‘valid’. Unfortunately they include some which blatantly don’t. Of course it’s always easy to nit-pick details, but an example, from the guidance, of exactly not assessing what you think you are assessing is, ‘I can prove air exists’ (now there’s a fine can of worms!) which should result from an assessment on being able to prove something about air, not the actual assessment criterion ‘to know air exists’ (really? In Year 5?).

1. Ongoing formative assessment

This is all about pupil and peer assessment and also full of some discomforting old ideas and lingering catch phrases. I admit, I’ve never been keen on WALTs or WILFs and their ilk. I prefer to be explicit with my expectations and for the pupils to develop a genuine understanding of what they are doing rather than cultivate ritualised, knee-jerk operations. Whilst I concede that this model focusses on assessment, it’s not very evident where the actual teaching takes place. Maybe it is intended to be implied that it has already happened, but my concern is that this would not be obvious to many teachers. The guidance suggests, instead, that teachers ‘provide opportunities’, involve pupils in discussions’, ‘study products’, ‘adapt their pace’ and ‘give feedback’. I would have liked to see something along the lines of ‘pick up on misconceptions and gaps in knowledge and then teach.’

Most disheartening, is to see the persistence of ideas and rituals to do with peer assessment. Whilst peer assessment has come under some scrutiny recently for possibly not being as useful as it has been claimed, I think it does have a place, but only with some provisos. In my experience, the most useful feedback comes not when we insist that it’s reduced to a basic format (tick a box, etc.) but when pupils can genuinely offer a thoughtful contribution. As such, it has to be monitored for misinformation; the pupils have to be trained to understand that their peers might be wrong and this takes time. After fighting hard against mindless practices such as ‘two stars and a wish’, my heart sinks to find it yet again enshrined in something that is intended for primary teachers across the country.

2. Monitoring pupil progress

In this layer, we move from the daily activities which are considered part of ongoing, formative assessment, to the expectation that teachers are now to use something to monitor ‘progress’. This involves considerable sleight of hand and I would have to caution teachers and leadership to assume that they can just do the things in the boxes. Let’s see:

TEACHERS BASE THEIR SUMMATIVE JUDGEMENTS OF PUPILS’ LEARNING ON A RANGE OF TYPES OF ACTIVITY

When? To get a good range, it would have to start early in the year, particularly if it includes all the science coverage from the curriculum. In that case, summative judgements are not reliable, because the pupils should have progressed by the end of the year. If it takes place at the end of the year, do we include the work from the earlier part of the year? Do we ignore the areas covered up to February? If we don’t, do we have time to look at a range of types of activity in relation to everything they should have learned? Neither ongoing work, nor teacher observation, are reliable or fair if we need this to be used for actual comparative data.

TEACHERS TAKE PART IN MODERATION/DISCUSSION WITH EACH OTHER OF PUPILS’ WORK IN ORDER TO ALIGN JUDGEMENTS

Oh how I despise the panacea of moderation! This is supposed to reduce threats to reliability and I’m constantly calling it out in that regard. Here they state:

“Staff confidence in levelling is supported by regular moderation. The subject leader set up a series of 10 minute

science moderation slots which take place within staff meetings across the year. Each slot consists of one class

teacher bringing along some samples of work, which could be children’s writing, drawings or speech, and the staff agreeing a level for each piece. This led to lengthy discussions at first, but the process became quicker as staff developed knowledge of what to look for.”

Where to begin? Staff confidence does not mean increased reliability. All it does is reinforce group beliefs. 10 minute slots within staff meetings are unrealistic expectations, both in perceiving how long moderation takes and in the expectation that science will be given any slots at all. Whatever staff ‘agree’, it can not be considered reliable: a few samples of work are insufficient to agree anything; the staff may not have either science or assessment expertise to be qualified to make the judgement; more overtly confident members of staff may influence others and there may be collective misunderstanding of the criteria or attainment; carrying out a 10 minute moderation for one pupil in one aspect of science does not translate to all the other pupils in all the aspects of science we are expected to assess. It might also have been a good idea to vet this document for mention of levels, given that it was brought out to address their removal.

3.Summative reporting

A MANAGEABLE SYSTEM FOR RECORD-KEEPING IS IN OPERATION TO TRACK AND REPORT ON PUPILS’ LEARNING IN SCIENCE

I just want to laugh at this. I have some systems for record-keeping which in themselves are quite manageable, once we have some real data. Where we have testable information, for example, factual knowledge, they might also mean something, but as most of us will know, they quickly become a token gesture simply because they are not manageable. Very quickly, records become ‘rule of thumb’ exercises, simply because teachers do not have the time to gather sufficient evidence to back up every statement. I note that one of the examples in the guide is the use of the old APP rubric which is no longer relevant to the new curriculum. We made the best of this in our school in a way that I devised to try to be as sure of the level as was possible, but even then, we knew that our observations were best guesses. The recording system is only as good as the information which is entered, despite a widespread misconception that records and assessment are the same thing! I’m no longer surprised, although still dismayed, at the number of people that believe the statistics generated by the system.

I didn’t intend this to be a balanced analysis – I’d welcome other perspectives – and I apologise to all involved for my negativity, but we’re clearly still a long way from a satisfactory system of assessing primary science. The model can not work unless we don’t care about reliability, validity or manageability. But in that case, we need no model. If we want a fair assessment of primary science, with data on pupils’ attainment and progress that we feel is dependable, then we need something else. In my view, it only begins to be attainable if we make creative use of technology. Otherwise, perhaps we have been led on a wild goose chase, pursuing something that may be neither desirable, nor achievable. Some aspects of science are amenable to testing, as they were in the SATs. I conceded to the arguments that these were inadequate in assessing the whole of science, particularly the important parts of enquiry and practical skills, but I don’t believe anything we’ve been presented with has been adequate either. Additionally, the loss of science status was not a reasonable pay-off. To be workable, assessment systems have to be as simple and sustainable as possible. Until we can address that, if we have to have tracking data (and that’s highly questionable), perhaps we should consider returning to testing to assess science knowledge and forget trying to obtain reliable data on performance and skills – descriptive reporting on these aspects may have to be sufficient for now.